Could a plant ever eat a person?

Link to Science News Explores article

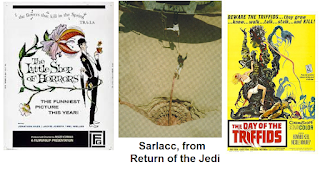

Monster and horror movies have their own versions of plant or plant-like creatures that devour people. In the 1960 movie The Little Shop of Horrors, a flower the size of a man was grown from seeds from a "Japanese gardener over on Central Avenue". It preferred human blood over regular plant food, for some reason. In the 1986 version Little Shop of Horrors, the plant came "from a Chinese flower shop during a solar eclipse". In 1963, a British movie came out (The Day of the Triffids) in which plant spores from space landed via a meteor shower, and they grew and regenerated and moved in order to eat people. A gigantic plant called a sarlacc grew naturally on the desert planet Tattooine in the Star Wars movie Return of the Jedi. It feasted on people, although it apparently digested them over a thousand years. But how possible are any of these concepts of plants devouring people?

First, consider the 600 + species of carnivorous plants that exist today. They are categorized into 5 major taxonomic groups, so they are not very closely related genetically. The International Carnivorous Plant Society (ICPS) gives three characteristics of plants that are labeled as carnivorous:

- They capture and kill prey.

- They have a mechanism to facilitate digestion of the prey.

- They derive a significant benefit (not a little) from nutrients assimilated from the prey.

- Active traps are triggered by some motion or touch of the prey, and the plant closes something around it.

- Passive traps don't rely on any prey motion.

- A third method uses a combination of active and passive trapping.

Trapped creatures die from exhaustion, or being smothered, or starvation. They are digested by enzymes that the plant (or bacteria inside it) makes, just like an animal stomach makes acid. At least fifteen types of enzymes have been found so far and specifically digest fats, proteins, DNA/RNA, chitin/sugars, etc. Some carnivorous plants merely collect an animal's feces and eat that instead of the animal.

What would it take to trap and digest a human being? The Science News Explores article goes into that with some scientific, not science fiction, background.

Such carnivores would obviously have to be large enough to trap someone. The largest in nature is a pitcher plant 16.1 inches (41 centimeters) tall with a capacity to hold about 9 gallons (3.5 liters). The most likely plants to evolve large enough would be the pitfall, sticky, or snap variety. The pitfall would need to be enormous, though, and its slippery interior would initially prevent escape. If it filled with rain water, that might drown the victim first, but it would also dilute digestive enzymes.

The article says a "giant flytrap would need massive amounts of energy to move electrical signals across its hefty leaves and also produce enough enzymes to digest a human". Until a person blunders into the plant, it would also have to exist without our body's nutrition, too, and that means an alternative source of energy.

Professor Barry Rice of the University of California - Davis figures that in order to conserve energy, a man-eating plant wouldn’t move but instead would stay in one place unlike the movie character triffids. But digestion of something as large as us would probably take so much time that bacteria would probably rot the body faster (and that might mean from the inside as well as outside). Rotting flesh could damage the plant that has trapped it.

Professor Adam Cross from Curtin University in Bentley, Australia thinks we would be strong enough to fight our way out of snap traps and pitfall traps. His ideal killer plant would be the plain sticky variety like a sundew with many tentacle leaves covered in glue-like material which would continue to latch onto a person as they struggle to escape. Eventually, one would just tire a person out.

But what attracts insects and other small animals in the first place to a carnivorous plant, and what would be needed for a human? Currently, some carnivorous plants produce attractive scents or display fake flowery colors to bring their prey in. Some are camouflaged with their surroundings. Others like the bladderwort rely on creatures to float nearby naturally until they stimulate the hair triggers that open the pore to suck them in. Humans would have to be fooled by camouflage for an accidental trapping. Or as Prof. Cross suggested, the plant would have to provide a delectable fruit or source of water that a person felt was needed, and then get trapped. So survival training would be necessary in order to identify the danger and avoid being eaten.

YouTube video of a sticky plant (Sundew) enveloping its prey.

YouTube video of a bladderwort (Utricularia) sucking in its prey under water.

YouTube video of Genlisea with Y-shaped lobster-claw leaves.

No comments:

Post a Comment