Louis Pasteur, the Father of Immunology

Born in France on December 27, 1822, Louis Pasteur began life as an average student but with a strong desire to learn. At first, his interests were in pastel sketching and fishing, but he aspired to attend a teachers college called École Normale Supérieure. To pay his way, he earned money by teaching math and physical science to high school children. His interests in science began when he was fascinated by

lectures from French chemist Jean-Baptiste Dumas at the College of Sorbonne (Paris College of Theology). These were public lectures that attracted 600-700 people at a time. Pasteur was accepted to École Normale in 1843 where he took up chemistry.

Louis Pasteur had once been thought to be a slow learner, but the truth is, he simply concentrated very carefully on everything he studied: "...he never affirmed anything of which he was not absolutely sure" (translated quote from The Life of Pasteur, by Rene Vallery-Radot). It was said that he didn't even know what it was like to skim a book because he wanted to get everything out of it. He was never satisfied with just book knowledge, though. At college, for example, they taught that phosphorus comes from extracting the mineral from bone. But he was so curious about the method they described that he bought some bones, burned and crushed them, and did the extraction himself just to have a phosphorus sample of his own!

After getting his bachelor's degree in 1845, he taught as professor of physics at the Collège de Tournon, but returned to École Normale at the urging of an old teacher. There, he got his doctoral degree in sciences in 1848 with a dissertation in chemistry and in physics. His studies focused on optical properties of chemicals, especially crystals. Pasteur was then appointed professor of chemistry at the University of Strasbourg.

His initial interests in chemistry were about the crystal structure of two chemicals and how they responded to polarized light. But he was also dedicated to showing students the practical side of their studies. As professor of chemistry and dean of the science faculty at the University of Lille, he arranged for factory tours so students could see firsthand iron foundries and steel & metal works factories, then ask questions to the foremen. This was his attempt to instill curiosity in students. His sentiments were reflected in a quote from a university speech, "In the fields of observation, chance only favors the mind which is prepared".

But he was as honest as any scientist could be. In his own experiments, he would scribble a note in his lab reports where he found mistakes had been made. If the hypothesis itself for the work was incorrect and lead to a false result, he would write "erroneous" when the experiment failed.

In 1854, he became dean of the new faculty of sciences at the University of Lille in northern France. At that time, fermentation of beer and wine was considered a chemical process, not something caused by the metabolism of yeast. As early as 1837, Cagniard de la Tour, Theodor Schwann, and Friedrich Kützing independently proposed that yeast was a living organism that multiplied during fermentation, but most people disagreed. The thought of the day was that the chemical change of sugars to alcohol was caused instead by some "vital" or "catalytic force", even by "unstabilizing vibrations" of the chemicals. But the three researches above observed yeast cells budding under the microscope and suggested its role in the process, but they couldn't explain further.

A year later, his attention was drawn to souring of milk, too. But he observed in beer and wine tiny globules even smaller than yeast were what was responsible for failed fermention into alcohol and instead generated acids. (These were eventually explained as bacteria.) His own university colleagues didn't read his paper for 3 months, so he grew dissatisfied at Lille and accepted a director position at the École Normale.

Pasteur showed how yeast were not only alive but that they actively changed sugar into alcohol.- He noticed that yeast cells multiplied during the fermentation process.

- When he sterilized sugar solutions and prevented yeast from entering, no alcohol was made.

- As sugar was consumed, yeast cells grew in number, and alcohol and carbon dioxide were produced.

- The alcohol and other products in fermentation bent light in a way that only living organisms can do.

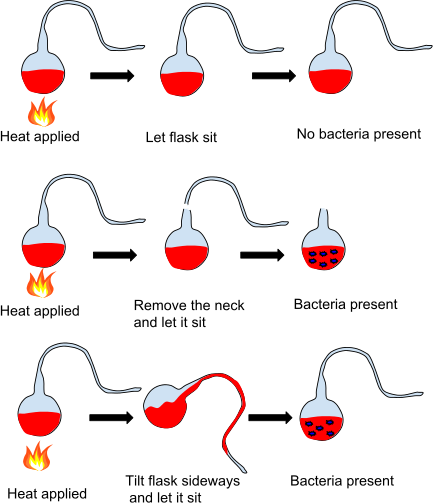

Pasteur then attacked the notion of spontaneous generation, that is, the formation of life from organic matter and not from a previous life. Lazzaro Spallanzani (1768) boiled broth and then sealed it; no bacteria grew in it, but critics said it needed air. Franz Schulze (1836) boiled broth and introduced air that had been bubbled through strong acids and alkali; nothing grew, but people claimed the "vital force" in air had been altered with the chemical treatment. Theodor Schwann (1837) repeated the work, then passed heated air into the boiled broth instead, but even though nothing grew, naysayers claimed the "vital force" in the air had still been changed by heating.

In 1859, Pasteur challenged these claims in a letter to naturalist Felix Archimede Pouchet, who believed in spontaneous generation:

In 1849, the silk industry in France was decimated by a disease of the silkworms. A solution could not be found, and healthy silkworms could not be imported because the disease was worldwide. The

French Department of Agriculture asked Pasteur to investigate even though he knew nothing about the industry nor that worms could even have diseases. From 1865 to 1870, he learned that there were two diseases, and only by selective breeding of eggs from worms that appeared healthy did he eliminate the problem and create fresh healthy stocks. But he also noticed that there were environmental factors that contributed to spreading the diseases, a point that stayed in his mind about other diseases. During his research at this time, Pasteur suffered a cerebral hemorrhage that paralyzed his left side. He was incapacitated for 3 months, during which time people had to read and write for him, but he kept pursuing the silkworm research.

In addition to the pasteurization process, Pasteur is most widely known for his role in vaccine development. In the 1870s, scientists were still unsure about the cause of many diseases from bacteria or viruses. They couldn't understand how things so small could have such a large effect.

Recognizing the power of vaccines, he then searched for a disease that affected animals and humans, so he could do his testing on animals before using the final vaccine product on people. He chose rabies, which had been known for 4,000 years even though the exact cause (a virus) was not known. The disease reaches the nervous system and eventually causes death by encephalitis.

Then, on July 6, 1865, a mother and her 9-year-old boy Joseph Meister arrived at his home after a 470-km journey. The boy had been bitten two days earlier by a rabid dog, and she sought Pasteur's help. He reluctantly instructed two doctors how to perform the 12 inoculations needed over the next ten days and worried so much that he could not work. But the boy survived, and the first human trial had been completed successfully.

He later proposed building an institute specific for the administration of the vaccine, and it later grew into the prestigious Institut Pasteur which spread worldwide. He won many accolades throughout his life and died on 28 September 1895.

If you wish to see a movie about his life, starring the actor Paul Muni, go to this YouTube link.

No comments:

Post a Comment